The artist presents his latest works to us until August 31, 2014, at the M.A.M.A.C, focusing on recent events in Middle Eastern countries, those of the Arab Spring. Stéphane Pencréac’h addresses this theme through four cities: Tunis, Cairo, Timbuktu, and Tripoli.

Four countries cruelly affected by revolutions that have overthrown dictators. The theme is not to judge, advocate, or defend one cause or another.

Stéphane Pencréac’h does not want to engage in propaganda and wishes to remain ambiguous. Each person must form their own opinion, define themselves. There is no Manichaeism; not everything is black and white.

The artist draws inspiration from historical events, such as the young man who set himself on fire in Tunis. The photo circled the globe, and the painter takes it up, making his painting a more poignant witness than the photo. He incorporates poetry, making it more eloquent and succeeds in evoking emotion. Timbuktu, with this woman and her deceased son, presents another triptych, especially a pieta that grabs you by the gut. In Cairo, the crowd parades with mad joy and hope, finally in front of freedom.

But death would be present with Anubis lurking in the corner, claiming the dead. Then we are in Tripoli, Libya, witnessing the end of a despot and his victims, including the man hung by his feet. The small story joins the larger one with portraits of the French president and the Libyan dictator. The city is split in two by walls, a child escapes the bombs, one might think of Delacroix and Gavroche.

His paintings seem to obey a mirror game except that the reflected image is distorted. In fact, one should read rather than simply look at Stéphane Pencréac’h’s paintings. Much like the bas-reliefs of cathedrals, they deliver, in a spiritual reading, a message—the cry of hope from these peoples in search of freedom, thirsting for new air.

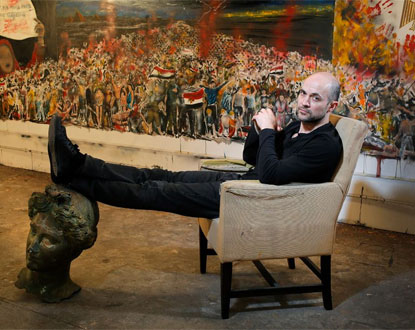

The creative process of the four triptychs is unveiled, the artist showing, in some ways, the genesis of his paintings: drawings, photos, sketches, studies, all testifying to a long maturation before presenting his work to the critical eye of the public. His painting has something religious about it, a feeling confirmed with the bronze bust of Mohamed Bouazizi, both winged angel and holding a dove in his left hand—symbol of peace or the Holy Spirit? Stéphane Pencréac’h leaves it to us to answer;

Upon viewing once more, but one could stay a day, these four paintings, we find the answer. We leave it to you to discover it for yourself.

Stéphane Pencréac’h and his historical paintings on the Arab Springs should not only be looked at but read—an instructive reading to better understand the history.

It is first and foremost a painting of history, and one must truly visit this exhibition to understand the soul of these peoples and the meaning of their revolts, whose embers are not yet extinguished.

Thierry Jan